As South Africa reflects on three decades of democracy, it is important to ask whether the country’s cities have changed for the better when it comes to racial mixing.

During apartheid, housing developments in South Africa were legally segregated along racial lines. Black Africans were forced into housing units on the outskirts of the city, while white residents lived in the suburbs closer to facilities and employment. This established negative spatial, economic, and social outcomes among racial groups.

Democracy in 1994 provided an opportunity for new housing developments to become more racially mixed. But is it?

Read more: Persistent inequality has many young South Africans questioning Nelson Mandela’s choices – Podcast

A recent study investigated whether South Africa is achieving spatial transformation by allowing different ethnic groups to legally mix in neighborhoods.

The short answer is “no.” While some new housing developments in Gauteng have improved racial mix, many others have not. Expansion projects near the township (a residential area set aside exclusively for black people) still house poor black African residents. Although suburban expansion for wealthy residents is racially mixed, economic inequality between racial groups remains pervasive.

This isolation leaves some groups cut off from employment opportunities and urban amenities. These residents face many costs (such as transportation costs) to find and keep jobs and access some facilities in the city far from their homes.

The result is a continual cycle of separation and inequality. To break this cycle, South African cities need fundamental spatial transformation.

the study

Overall, the level of racial mixing has increased since the advent of democracy. In Gauteng, the country’s economic capital, many once white-only suburbs have been desegregated. This represents some progress towards a post-apartheid racially equal society. But what about new residential areas?

My research required two things. It’s spatial data on decades of housing development and recent population estimates for various racial categories. We then used the racial segregation index to calculate the racial diversity of all residential developments built in Gauteng since 1990.

During this period, Gauteng’s residential area increased by approximately 905 km², creating many opportunities for racial mixing and spatial transformation. However, my research shows that new housing developments tend to replicate the racial diversity of the neighborhoods from which they expand. And most of the residential expansion will take place on marginal land around the township. This actually reduces racial diversity across the state.

The study of racial diversity provides valuable insights into the changing geography of apartheid since democracy.

Survey results

We found that ethnic diversity in new housing developments in Gauteng is now even lower than it was in 1990. Therefore, new housing developments in Gauteng do not, on average, lead to further racial mixing. Of those living in residential areas developed after 1990, 80% live in neighborhoods with little racial mixing, or less than 10%.

Map: Christian Hamann

However, there is considerable variation between states (see map above). Desegregation (racial mixing) is occurring in many areas. However, new housing developments with low and high racial diversity are still far apart from each other on the map. For example, Johannesburg’s more affluent northern areas are highly ethnically diverse, with people of all races living in new housing developments. Racial diversity is low in poorer parts of the South.

On the map, new housing developments are shaded based on racial diversity. Light yellow areas have low racial diversity, and dark purple areas have high racial diversity. It is easy to see that areas added next to townships, such as Mamelodi in Pretoria and Soweto in Johannesburg, have lower ethnic diversity.

But the proportion is higher in areas that were added next to formerly white-only suburbs, such as Menlyn and Randburg. The growing racial diversity here is directly related to the increase in townhouse, multifamily, and semi-detached housing developments. Middle and high income people live here. Still, some of these developments lead to increased racial mixing, while others do not.

Is class mixing increasing?

Another purpose of the study was to try to understand whether increasing racial mixing also increases class mixing. Does it have a positive impact on socio-economic sorting? Research highlights growing inequality and socio-economic sorting in many cities around the world. For example, cities such as Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Istanbul are increasingly shaped by socio-economic classifications.

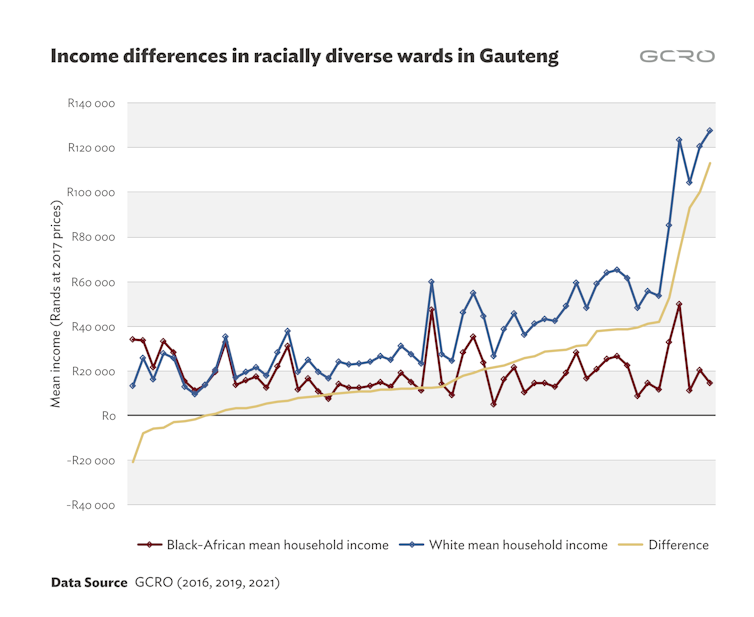

Graph provided by: Christian Hamann/GCRO

My research shows that in racially mixed neighborhoods, the average household income of white residents is significantly higher than the average household income of black African residents (see chart above).

Therefore, despite desegregation, income inequality in neighborhoods remains high. Research case studies also demonstrate how housing affordability and the social nature of neighborhoods influence class mix. For example, affordable housing often leads to more mixed housing neighborhoods, whereas this does not occur in upper-class markets with more expensive housing.

Therefore, while we cannot assume that wealthy neighborhoods contain only one racial group, as they once did, we also cannot assume that there will be socio-economic equality in newly racially mixed neighborhoods.

Despite 30 years of gradual racial mixing in the once white-only neighborhood, spatial change has been slow. And the relationship between space and class in Gauteng has not changed significantly. Housing expansions generally reproduce the racial and socioeconomic composition of the neighborhoods from which they expand.

what does this mean

This study highlights that opportunities for racial and socioeconomic integration can only be created at a very local level if neighborhoods are provided with diverse housing options. In other words, new developments need to cater to a wider range of income groups. For example, luxury townhouses need to exist alongside more affordable apartment and public housing developments, such as those happening in suburbs like Cosmo City and Fleurhof.

Read more: South African media has been free for 30 years and has done a good job, but more diversity is needed

Public housing programs and post-apartheid housing policies give us hope that this can still happen. Public housing efforts must provide affordable housing in close proximity to areas of economic opportunity. Public policy must ensure that a person’s place of residence does not become the greatest (and most impossible) burden to overcome for a better life.