In 2014, the South African government announced a new direction for housing policy. The aim was to phase out small-scale, low-cost housing projects of a few hundred units and focus solely on megaprojects, which are new residential areas that combine large numbers of housing units and numerous social amenities.

Housing provision has been a major focus since 1994, given the unequal access to housing as a result of apartheid. A 20-year government study from 1994 to 2014 reported that 3.7 million subsidized housing opportunities were created, no doubt a remarkable achievement.

Nevertheless, in 2014 the then Minister of Human Settlements Lindiwe Sisulu expressed extreme concern that housing production was declining. This left 2.3 million households unpaid. Ministers supported megaprojects (also known as catalyst projects) as a way to get supply back on track.

Large-scale human settlement projects were not entirely new to South Africa. Some homes were already in advanced stages of construction in 2014. What was new in this announcement was the idea that all housing would be provided solely through the construction of nationwide megaprojects. From 2014 to 2017, the Ministry of Human Settlements created a list of 48 catalytic projects, which were completed last year.

In a recently published academic paper, we argue that this policy was underdeveloped. The megaproject approach quickly moved from announcements to discussion documents and frameworks to the creation of a list of large projects. Much of this process took place behind closed doors, with little consultation. And there was little room to consider the limitations of the megaproject approach or the merits of alternatives such as small-scale urban reclamation projects.

Nevertheless, this paper attempts to explain the acceptance of the megaproject idea in the human settlements field and understand the motivations and agendas of those who promoted it.

Rationale for megaprojects

Megaprojects in the broadest sense are attractive because they are much more visible and memorable than smaller, diffuse projects. As a result, politicians will be able to brand their policies more effectively. Megaprojects convey a sense of decisive action, in which states can exert their power in large-scale interventions.

shutter stock

More specifically, proponents of the megaproject approach believed that larger projects could deliver more housing faster. When announcing the policy in 2014, then-Human Settlements Minister Lindiwe Sisulu said the megaproject would deliver 1.5 million homes by 2019.

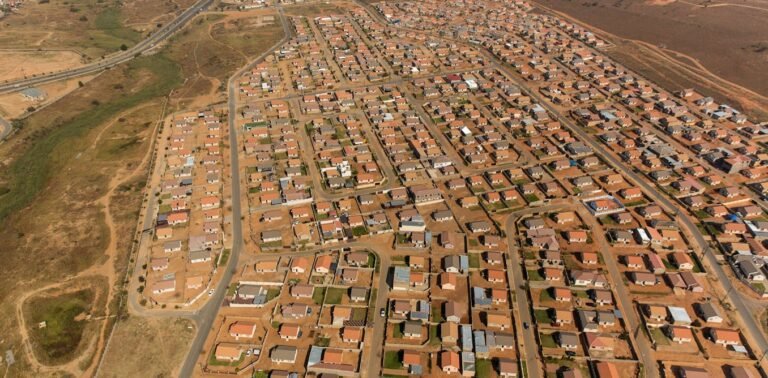

Some proponents of the megaproject approach, particularly the Gauteng provincial government, were particularly attracted to the idea of creating entirely new ‘post-apartheid cities’ that could meet the country’s ‘live, work and play’ needs. Starting anew with new settlements would be a way to design urban spaces to avoid the inequalities and inefficiencies that plague existing cities. They will also bring large projects to poor regions with little else to spur significant economic growth.

The megaproject was also aimed at solving various governance issues. In particular, managing the 11,000 human settlement projects in various stages across the country was extremely difficult. Consolidating these into just a few dozen projects was a way to focus the government’s attention and reduce administrative burden and costs.

The megaproject approach also appeared to be a way to manage the division of labor and tensions between different areas and different departments of government. Some local governments began to take greater responsibility for housing projects, and national and state governments saw megaprojects as a way to more centrally manage housing.

concerns

Some critics are more concerned about the size of the project than the fact that it may be in a poor location. The main reason is that land in better locations is more expensive. Furthermore, there is not a lot of land in good locations to accommodate new settlements of this size.

The history of attempts to build new towns shows how difficult it is to create new urban centers that can provide enough jobs for the people who live there. The same goes for mega-projects, and there are concerns that if construction jobs disappear, residents will have to pay for long-distance travel to jobs outside their area of residence.

Megaprojects on the periphery of cities also run counter to plans expressed in various policy documents to reduce urban sprawl and densify existing cities. There are other challenges in the surrounding area as well. If new projects are located far from sewer, water, electricity, and roads, there will be significant financial and environmental costs.

Other concerns focus more directly on large new projects. Large projects can take years to get off the ground, so delivery can be disrupted for long periods of time.

Toward a balanced policy

In a recent speech to Parliament, new Human Settlements Minister Noma Indiya Mfeket said catalytic projects “worth more than R5 trillion” had been launched. But she also announced that the budget has been “significantly reduced” as a result of the financial challenges facing the state.

We believe that at this point we should be given an opportunity to reflect a little on the direction of our four-year-old megaproject. This review should consider whether all housing should be provided in megaprojects, as the policy was originally intended, or whether projects of various sizes should be encouraged, particularly to facilitate urban reclamation projects within existing urban areas.

Proposed megaprojects should be evaluated with respect to their location, total cost to the state, and long-term sustainability. Some are moderately accessible, while for others the economic opportunities are marginal and marginal at best. South Africa cannot afford to build housing in spaces with few economic prospects and limited benefits for city residents and the country.