From the refineries of Port Harcourt to the frenetic markets of Kano, from the commercial hub of Onitsha to the corridors of power in Abuja, Nigeria is an economic powerhouse buzzing with activity, trade and wealth. However, in the eyes of the state, much of this dynamism remains invisible. This is a contradiction in Africa’s largest economy. This country generates wealth everywhere, yet struggles desperately to turn it into public revenue.

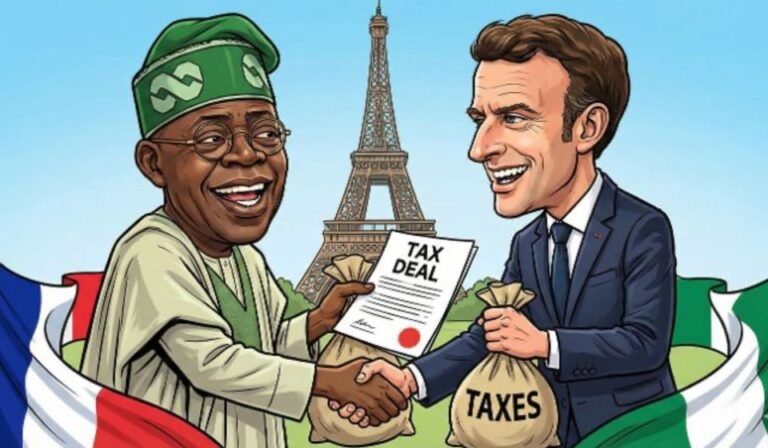

To break this cycle, the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) has taken a historic and controversial step. On December 10, the company signed a memorandum of understanding with the French tax authorities. The goal is to deploy artificial intelligence in Paris to reveal what the human eye of Nigerian tax officials cannot see. But behind the promise of efficiency looms the shadow of a calculated risk, handing over the keys to economic sovereignty to former colonial powers in exchange for liquidity.

To understand the seismic significance of this agreement, we need to look at the deep fault lines that run through Nigeria’s economy. The country’s tax-to-GDP ratio has historically hovered around 10 percent, one of the lowest in the world and well below the average for sub-Saharan Africa. The system is crippled by a paralyzed dual-speed economy. On the one hand, there is the formal sector, dominated by large multinational corporations in oil, telecommunications, and banking, often masters of sophisticated tax avoidance. On the other side is the vast ocean of the informal economy, estimated at around 65 percent of GDP, a parallel world of cash transactions and commercial empires that leave no digital footprint and make millions of economic agents virtually invisible to tax authorities.

It is in this context of administrative incompetence that French technology enters the field. The agreement does not include the deployment of human auditors or staff, but rather the introduction of predictive algorithms and automated audit systems. The technology promised by Paris will work like a digital dragnet, cross-referencing banking data, real estate purchases, energy consumption and customs movements to uncover discrepancies.

The real impact will be immediate and surgical, striking at the two main arteries of tax evasion. Consider the transfer pricing system used by multinational corporations. In the past, large companies have been able to transfer profits earned in Nigeria to their European headquarters and justify it as the cost of fictitious services and consultancy fees, thereby hollowing out local tax bases. Using new AI tools, Nigeria’s tax authorities will be able to analyze millions of global transactions in real time, compare declared values to international benchmarks, and trigger automated alerts on any anomalies.

At the same time, this technology will shed light on the dark side of the domestic economy. Large traders who move containers of goods across land and port borders without registering on the tax register will no longer be able to hide. The algorithm cross-checks lifestyle indicators, asset ownership, and indirect financial flows to reveal gaps between declared income (often zero) and actual accumulated assets. For the first time, tax evasion is no longer a matter of clever concealment, but a mathematical impossibility.

But while the diagnosis may be accurate, Abuja’s treatment of choice raises thorny geopolitical questions. The agreement provides for the sharing of aggregated economic data with France. While FIRS guarantees the protection of sensitive data of individual taxpayers, granting access to macroeconomic “big data” will essentially give Paris a real-time view of the health of the Nigerian economy. This allows foreign powers to understand cash flows, sectoral vulnerabilities, and market trends faster and better than domestic policymakers in Nigeria.

This move also signals a shift in France’s African strategy. As military bases across the Sahel close and Paris’s campaigning influence wanes, France appears to be re-entering through a digital window, repositioning itself as an indispensable technological partner rather than a gendarme. It’s the rise of a kind of soft power built on servers rather than soldiers.

Nigeria is thus at a historical crossroads. Nigeria has chosen to sacrifice some degree of sovereign secrecy at the expense of fiscal efficiency, betting that increased revenue will justify the costs of long-term technology dependence. It remains to be seen whether this “asymmetric transparency” will deliver the promised development or transform Nigeria’s tax system into a permanent customer of European technology.