South African state-owned enterprises have seen a significant decline in fixed investment over the past decade, with public-private partnerships seen as the only way to increase investment.

STANLIB economist Ndivuho Nshitenze said fixed investment in South Africa had declined by an average of 1.3% over the past 10 years.

Although South Africa has an excellent national economic infrastructure network, this infrastructure has deteriorated significantly in recent years and new networks have not been sufficiently developed or expanded.

The National Development Plan drawn up in 2012 sought to address this problem by setting an ambitious target of increasing fixed investment spending to 30% of GDP by 2030.

However, as of Q3 2024, fixed investment in SA was only 14.8% of GDP, with the private sector accounting for the majority of this investment, at 10.6% of GDP.

This is not only below policy targets, but also by historical standards.

“In effect, SA has missed out on capital investment in roads, rail, ports, electricity, water, sanitation, public transport and housing by a generation,” Neshitenze said.

“To ensure sustained economic growth and improved services, public sector infrastructure investment must increase significantly from current levels.

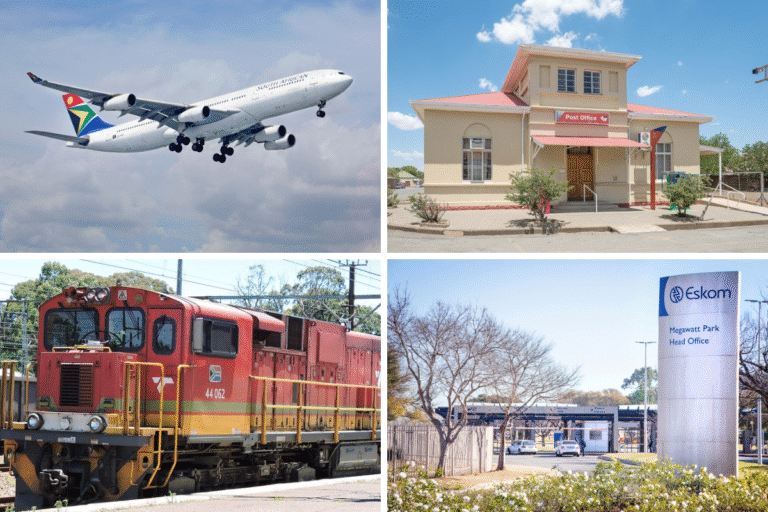

“Given that state-owned enterprises are tasked with providing economic infrastructure, at least half of this responsibility falls on companies such as Eskom, Transnet, Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority (TCTA) and SANRAL.”

However, there are major constraints on the ability of state-owned enterprises to achieve their goals.

The investment shortfall is too great, and state-owned enterprises lack the funds and capacity to meaningfully increase infrastructure spending.

Since its post-democracy peak in the fourth quarter of 2013, fixed investment by state-owned enterprises has fallen by almost 50%.

To return investment to peak levels, SOEs would need to increase their current investment spending by R134 billion (based on 2023 GDP levels).

However, the R240 billion increase needed to reach the target of 5% of GDP for state-owned enterprises will still be significantly lower.

“This level of investment needs to be maintained for about five years to ensure sustainable economic growth,” Neshitenze said.

“This means that state-owned enterprises alone will need to spend R1.75 trillion over five years to address SA’s infrastructure problems.”

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the balance sheets of the country’s key state-owned enterprises have deteriorated over time, with many of them in serious financial distress.

Many are unprofitable, increasing unsustainable debt accumulation and requiring large-scale government bailouts.

The debt levels of the 10 largest state-owned enterprises increased by R313.6 billion between 2012/13 and 2022/23, and the government had to provide a similar amount of relief.

Therefore, there is little room for additional debt or government aid to fill the fixed investment spending gap.

what to do

However, the government has committed to increasing the level of infrastructure spending in the medium term, with the aim of increasing private sector participation.

National Treasury is implementing recommendations to improve the policy, legal and regulatory framework for public-private partnerships (PPPs).

The government recently introduced amendments to the Finance Act to reduce red tape for projects valued at less than R2 billion involving PPPs.

PPP implementation increased in 2023/24, with 15 projects in the initiation stage and 19 projects in the feasibility study stage. Ten projects are also ready to begin the procurement process.

“This is a welcome gesture by the government, but it is not enough to fill the investment gap,” Neshitenze said.

“Furthermore, the implementation of infrastructure projects by governments is often hampered by poor coordination within the public sector, lack of cooperation with the private sector, and high borrowing costs.”

Although the government has pledged to increase the use of PPPs, they represent only 2% of the total infrastructure spending planned in the medium term of R19.1 billion.

This means that most infrastructure spending plans are built on already strained public sector balance sheets.

South Africa needs further fixed investment to extend its long-term growth trajectory, but the public sector, particularly the state-owned enterprises involved, do not have the financial capacity to implement the investment plans necessary to build infrastructure on the scale required.

“Given the constraints, the only option left for the government is to attract private investment more aggressively,” Neshitenze added.

“This can be achieved by ensuring policy certainty, improving business confidence and making greater use of PPPs.”