South Africa needs to think differently about housing and urban development.

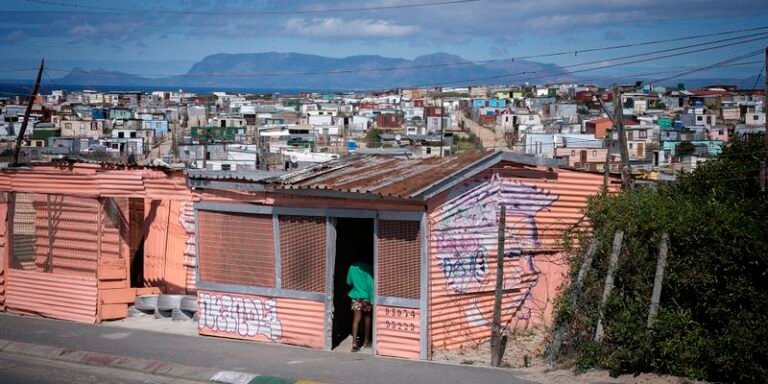

Current policy has delivered millions of RDP units at a rate that experts agree is far superior to public housing programs in most other countries. However, South Africa’s approach of building RDP houses far from centers of economic activity, with limited access to decent schools and functional infrastructure, reinforces the spatial pattern of apartheid and contributes to alarmingly high unemployment rates. Many of the poor people living in these remote areas cannot even afford to travel to find work.

The commitment to provide fully subsidized independent housing to all South Africans with a monthly income of less than R3,500 meant that the government needed access to vast amounts of undeveloped land for RDP housing projects. Generally, such land was located on the outskirts of cities and towns. With population growth and rapid urbanization, this is no longer a viable or affordable strategy.

Even if the financial situation improves, the costs of a “greenfield”-centered approach could bankrupt cities. Urban sprawl, transportation costs, and environmental costs will have a devastating impact on the financial viability of cities even before major infrastructure investments are made.

Harvard University professor Ricardo Hausmann argued that in countries where housing shortages are measured in housing units rather than locations, solutions often don’t solve the real problem. For him, “home is an object, and habitat is the nexus of many overlapping networks, including power, water, sanitation, roads, transportation, labor markets, retail, entertainment, education, health, family, friends, and safety.” These networks complement all the benefits of agglomeration that help cities create opportunities for low-income households and individuals, thereby promoting local economic development and more inclusive growth.

Compare this with the approach of creating generally isolated and poor areas where mainly unemployed and unskilled people “live in isolation, cut off from other people”. All this makes it difficult for them to benefit from a connected urban economy.

It’s time to think differently.

Significant opportunities exist in densifying existing suburbs using what is known as a “big, small” approach. It refers to the process by which poor households and small- to medium-sized private developers densify existing residential areas by building multifamily rental housing or by constructing additional low-cost rental housing in backyards. These small-scale developers provide rental housing (and sometimes sectional ownership) close to centers of economic activity, while promoting local economic development through the use of small-scale builders and other contractors.

A “big, small” approach to housing policy emphasizes the creation of connected, dynamic neighborhoods over multifamily housing.

This bottom-up, market-driven approach is gaining momentum across South African cities. And if enough “small” developments occur simultaneously, the impact can be “huge.” People want to live in prime locations in cities where jobs and opportunities are concentrated. They are willing to replace long and expensive commutes and pay affordable rents for relatively small spaces, provided the accommodation is well-located.

Small entrepreneurs are responding to this significant demand by developing relatively inexpensive (mainly) rental options. Hillbrow, Yeovil, Orange Grove and Malvern in Johannesburg and Khayelitsha, Delft and Dunoon in Cape Town are all close to transport corridors, local economic nodes and city centres, and are just some of the areas where these developments are taking place. The process by which homeowners, landlords, and small developers build properties near economic opportunities in urban areas, primarily for rental purposes, is proliferating.

Pioneers in this field are TUHF Grouphas been in operation for 17 years and currently operates in city centers across all eight metros. During this time, they have provided a total of R4.7 billion in funding to housing entrepreneurs. Furthermore, the supported investments made a significant contribution to local economic development.

This large-scale, small-scale approach has enormous potential to meet the city’s accommodation demands.

There are 4.5 million freestanding privately owned homes in South Africa’s metros, with great potential for densification. If recognized and supported, this increasingly prominent way of creating new low-cost housing options for the poor has the potential to reduce new land demand (and resulting urban sprawl) in metropolitan areas by at least 70% over the next 25 years. At the same time, we will create more efficient, productive and inclusive cities, offering far more opportunities for the poor in well-located areas.

Many of these private marginal developers rely on second mortgages, savings, unsecured personal loans, or rely on local informal lenders to finance their construction. Several new financial providers are emerging, including platforms such as iBuild, Indlu, uMaStandi, and Bitprop. They offer innovative and often risk-sharing financing solutions to developers who, due to limited assets or income, are ineligible for loan products offered by traditional banks.

But unless the city’s burgeoning supply of affordable accommodation is actively supported and managed, ‘big and small’ densification could lead to urban slums, worsening conditions in existing residential areas, and overburdening engineering and social infrastructure.

The challenge is that both local governments and incumbent banks have failed to align their regulations, services, and lending products to the realities of “big and small” densification and development. High compliance burdens, insufficient long-term development funding, and inadequate infrastructure combine to inhibit the emergence of large-scale, high-quality rental housing.

Managing this phenomenon is critical if South Africa is to ensure that the quality of these ‘bottom-up’ housing developments improves.

Metropolitan governments need to reevaluate and strengthen their policy positions on densification and backyard renters. Suburbs where density benefits housing seekers and the city should be identified and focused. Companies need to implement appropriate, streamlined (“off-the-shelf”) compliance requirements, expand their infrastructure, and strengthen their management capabilities in areas subject to this type of development.

The central government needs to enable densification through small-scale entrepreneurs. The state should consider introducing conditional state subsidies for South Africa’s metros. This would fund the cost of metropolitan areas to provide free service connectivity, exempt metropolitan areas from large infrastructure contributions from developers, and allow metropolitan areas to expand and upgrade metropolitan infrastructure. A portion of the grant could also be used to reconfigure planning and building compliance requirements.

Businesses, especially big banks, have an important role to play. They can speak out in support of these developments and help publicize what is happening. Incumbent banks will need to develop well-structured project and asset financing for “big and small” housing projects. There is also the possibility of providing further loans to support existing specialized financial institutions such as TUHF to expand their lending at acceptable interest rates.

South Africa must move away from apartheid-style cities where the poorest people are forced to live far from economic opportunity. This increases the scale of unemployment, prevents cities from connecting job seekers and employers in an efficient way, and leaves many people in poverty or dependent on social transfers.

Against a backdrop of mass unemployment, extreme fiscal constraints, and the devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the government’s interest is to encourage and enable the large-scale wave of private-sector-led development that is already occurring. If it is properly managed and developers are funded and meet reasonable compliance requirements, the result will be a significant contribution to regional economic growth and increased access to housing and other opportunities.

South Africa can create the cities it wants, with vibrant, well-managed, well-located and low-income neighborhoods, rather than inner-city slums. DM

Represented by Anne Bernstein CDE Matthew Nell is in charge. Shisaka. This article is based on a new publication from CDE. “Building Better Cities: A New Approach to Housing and Urban Development.”