Kalkidan YveltalBBC News in Addis Ababa

AFP (via Getty Images)

AFP (via Getty Images)The vastness of the construction site was initially overwhelming for the young Ethiopian mechanical engineer.

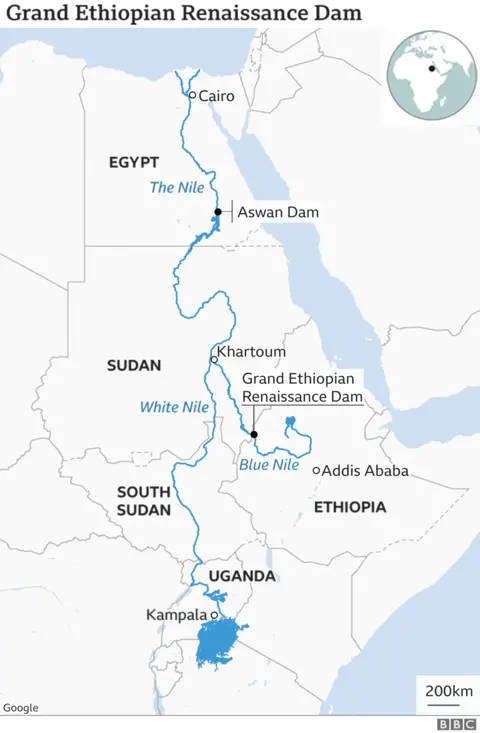

Hundreds of workers are already digging the foundations under difficult conditions for what is now Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam spanning the Blue Nile River. The dam will not only provide electricity to the region but also help electrify the country.

Moges Yesiwas was 27 years old when he arrived in a corner of western Ethiopia in 2012, eager to gain valuable experience in his field. Completion of the project will change his country, but it will also change his life.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed on Tuesday officially inaugurated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Gerut), hailing it as “the greatest achievement in black history.”

Abiy, along with Kenyan President William Ruto and Djibouti’s Ismail Guelleh, unveiled the plaque before turning on the turbines.

The walls span 1.78 km (1.1 miles) across the valley, are 145 m (475 ft) high, and are constructed from 11 million cubic meters of concrete. A huge reservoir was created called Lake Nigat, which means dawn in Amharic.

The construction of dams on the tributaries of the Nile, which supply most of the river’s water, was controversial among downstream countries. Diplomatic tensions with Egypt escalated, and there was even talk of conflict.

But for Ethiopia, the Gerudo has become a symbol of national pride, and in Abiy’s view, it has put the country firmly on the world stage.

On a personal level, Mogues, now 40, is also “very proud to be a part of it.”

“It was very fulfilling to see the dam progressing day by day. I came here looking for work, but halfway through it didn’t feel like work anymore. I grew attached to the project and worried about its future as if it were my own.”

There were also challenges.

“It was difficult being separated from my family for such a long period of time,” he told the BBC. Moges was only able to return to his home in Bahir Dar, a 400km drive away, only twice a year.

The remote location of the dam site and the extreme heat, with temperatures sometimes reaching 45 degrees Celsius, also posed problems. Furthermore, the working hours were long.

“Our shifts were from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., with only an hour lunch break. Then we handed over to the night staff, because we had to work 24 hours a day,” Moges said.

His job was to ensure that building work was structurally sound and building codes were maintained.

As the Horn of Africa country has been rocked by political violence and ethnic strife over the past decade, the Gert project has become a rare unifying force.

While some, like this engineer, worked directly on the dam, millions of other Ethiopians literally invested in it.

People from all walks of life contributed to the construction of the dam through donations and the purchase of government-issued bonds.

U.S. President Donald Trump claims Washington financially supported the dam’s construction, but Addis Ababa insists it was fully domestically financed.

AFP (via Getty Images)

AFP (via Getty Images)Several fundraising campaigns were held and the public made multiple donations.

Kiros Asfaw, a clinical nurse, was one of them.

Despite being from the Tigray region, which has been devastated by two years of civil war, he has contributed in any way possible to the construction of the dam since the plan was first announced in 2011.

He says he has purchased government bonds more than 100 times, but had to suspend purchases as basic services, including banking, were shut down in Tigray during the conflict.

Quiros’ motivation was rooted in the words of the late Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, who oversaw the project’s launch, that “all Ethiopians must come together to support the dam.”

“I promised myself I would do everything in my power to cross the finish line,” the father-of-five told the BBC.

Now that all the turbines are up and running, thoughts turn to what a difference that power will make to Ethiopia.

When fully operational, it should generate 5,100MW of electricity, more than double the amount the country would generate without the dam and enough to power tens of millions more homes in the country. However, it depends on whether the infrastructure is in place to supply electricity to different parts of the country.

Water and Energy Minister Habtam Ifeta told the BBC that almost half of the country’s 135 million people do not have access to electricity.

“This is what we want to reduce now over the next five years. Our intention is to have at least 90% of our country have access to electricity by 2030,” he said.

Getenesh Gabiso, a 35-year-old from Aramla, a rural village on the outskirts of Hawassa, Ethiopia’s main city in southern Ethiopia, is among those imagining the changes it could bring.

Her life reflects the lives of millions of people living in rural Ethiopia.

Getenesh has no electricity for her husband and three children, even though she has a small thatched hut with mud walls just 10 kilometers from Hawassa.

She collects firewood from a nearby farm for cooking.

For lighting, kerosene-fueled lamps are used. Her husband, Germesa Garcha, is worried about his family’s health.

“(Getenesh) used to have big, beautiful eyes, but years of smoke had damaged them and they became watery,” he said.

“I’m worried about what will happen if the children suffocate from the smoke.”

Amencisa Neguera/BBC

Amencisa Neguera/BBCGetenesh sometimes relies on the dim light from her husband’s cell phone when it’s dark, but her only dream is to be able to see at night.

“I want light in the house. I don’t care about any other appliances right now. All I want is light in the evening,” she told the BBC.

They are looking forward to the changes that Gert’s power will bring. But Government Minister Habtamu admits more needs to be done to expand the country’s grid infrastructure.

Tens of thousands of kilometers of cable still need to be laid to reliably connect small towns and remote villages.

But for engineer Moges, the electricity generated by the Blue Nile will ultimately make a difference.

He has a son who was born during construction of the dam.

“I really hate the fact that I couldn’t be there for him as much as I needed to,” he says. “But I know that his future will be bright because of my contribution, and I will be very proud to be able to tell him that when he grows up.”

Additional reporting by Hanna Temuari

Other BBC articles about dams:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC